what is the total number applicants at university of virginia and the ratio of men to women

Women take always lived, worked and learned at the University of Virginia, merely over the last century women have fundamentally transformed what once was known as a "Gentleman'south University." The increment in admission and opportunity for women has raised UVA'south bookish profile and enriched the educational and social experiences of all students.

Despite Thomas Jefferson's progressive vision of education in a newly formed nation, his plans for the University did not include women. Similar many of his era, he believed that women's teaching should be oriented toward the domestic, and the higher pedagogy he believed was the bedrock of republic and civilized public life was not extended to them.

Nonetheless, women found ways to learn at the Academy. Before 1970, more than 15,000 women earned professional, graduate and undergraduate degrees, and a comparable number received degrees or certificates from the Nursing School. In 1970, 450 undergraduate women enrolled in the College of Arts & Sciences, transforming the University into a fully coeducational establishment. Today, women constitute more than half of the pupil population. Women excel in the classroom, win prestigious awards and scholarships, compete in athletics and atomic number 82 educatee organizations. The University's alumnae are leaders and pioneers in every attribute of American life, and their contributions have reshaped a quickly irresolute world.

The various stories of private female students at the University trace a movement toward integration and empowerment on Grounds.

The Early Years

In 1880, UVA hosted the state'southward beginning Normal School, which provided instruction for schoolteachers throughout Virginia—including 312 women.

Caroline Preston Davis applied to take the examination for a B.A. in mathematics in 1892, simply the awarding was denied and she was awarded a document of proficiency instead. Ii years later, Addis Chiliad. Meade (Grad 1894) received a principal's caste in mathematics. That same year, the faculty and Lath of Visitors voted against admitting women under any conditions.

The School of Education established a summer school for teachers in 1907; women were admitted, but the courses offered were intended to satisfy requirements for instructor certification and did not atomic number 82 to degrees. Women could also take classes in home economics, cooking and stock judging—the examination of domesticated animals for convenance purposes.

Georgia O'Keeffe attended the University for four summers, taking classes and subsequently educational activity them betwixt 1912 and 1916.

northward 1920, the aforementioned year American women won the correct to vote, the Virginia Full general Assembly decided to acknowledge women to graduate and professional programs at UVA. Seventeen women enrolled at UVA in those programs in the fall of 1920, including Elizabeth Due north. Tompkin (Police 1923), who would be the first woman admitted to the Virginia State Bar.

By the 1930s, a few wives and daughters of faculty members were accepted as degree candidates in the College of Arts & Sciences. As well during this catamenia, Alice Jackson, an African-American adult female, applied to a master's program in French. When her application was denied because of Virginia's racial segregation education laws, she instead earned a main's degree at Columbia University.

1920: The University enrolls 23 women, constituting 1% of total enrollment.

1926: At 118 enrolled, women constitute five% of the University's total enrollment.

Co-ordinate Educational activity for Women

In 1910, Mary-Cooke Co-operative Munford lobbied the Virginia General Assembly to establish a co-ordinate women's college. A co-ordinate women's college would share some of UVA'due south resources, only maintain dissever learning environments for the sexes. The UVA kinesthesia endorsed the bill in 1911. Five years after, the bill passed the country senate, but failed in the House of Delegates by two votes. In 1930, the General Assembly decided that a co-ordinate higher should be at least xxx miles from Charlottesville. In 1944, Mary Washington College, which was 70 miles away in Fredericksburg, Va., became the women's liberal arts college associated with UVA.

When UVA became a fully coeducational institution, the amalgamation between UVA and Mary Washington came to an end. During the early '70s, more than transfer students came from Mary Washington to UVA than from whatever other school.

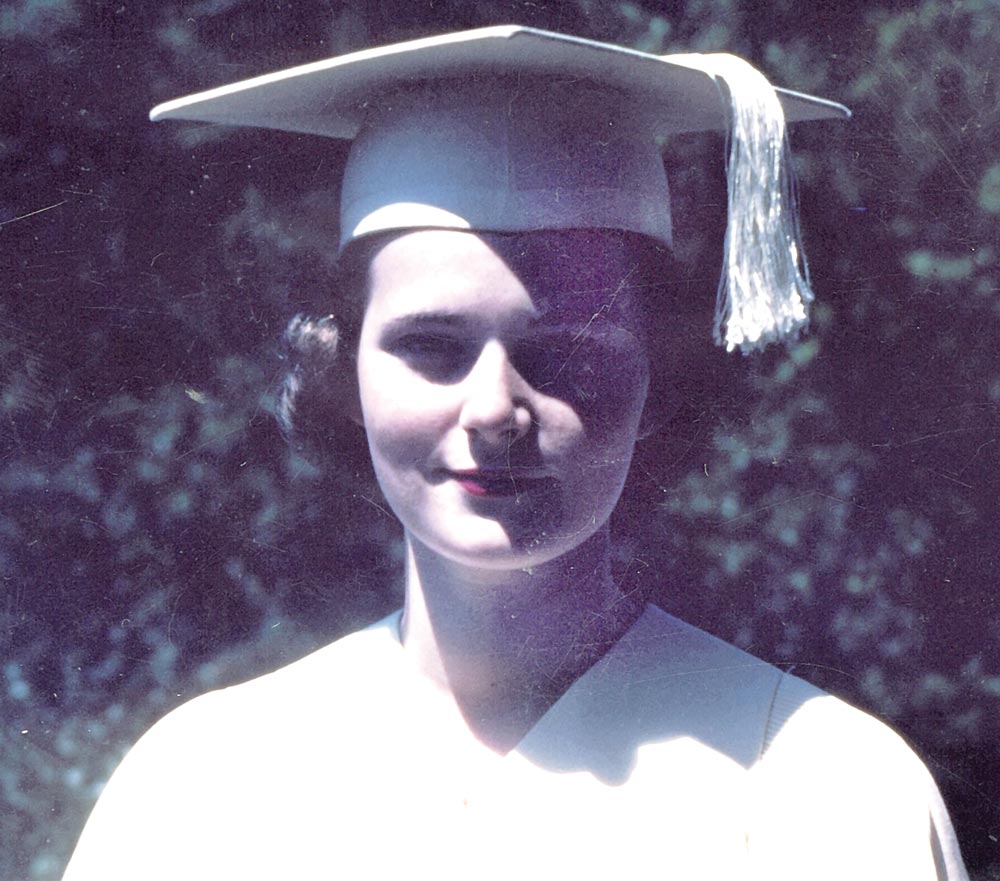

Constance Page Daniel

Constance Page Daniel (Col 1931) had an unusual opportunity to study at Cornell. "This rich woman came past my father'south office i mean solar day and said she had an interest in sending Southern women to Northern schools," says Daniel. Her male parent was mathematics professor James Morris Folio, dean of the faculty, and Daniel had grown up on McCormick Road in the heart of the University, but she moved northward and studied at Cornell until "the [stock market] crash came and there was no more money."

When Daniel returned to Charlottesville, her begetter said, "Nosotros're going to become you to be the outset woman to graduate in the regular winter school." At the time, women could nourish summertime classes and study nursing or education. There were female graduate students, simply undergraduate women in the College of Arts & Sciences were uncommon.

When reflecting on the news that more one-half of the students currently at the University are women, Daniel says, "I'm glad my father'south non here to see that. He idea women at the University were abomination." She laughs. "And I was the worst of all."

Growing upwardly on Grounds, Daniel's family had often hosted Sunday night dinner for students. She'd gone to dances at Mad Bowl and attended fraternity parties. "If y'all were a woman and could breathe, you usually had 4 or five men following 'circular behind yous," says Daniel. "So my social life was more than anyone could await."

Daniel's experience in UVA classrooms was less hospitable than her time as simply a faculty daughter. "When I'd walk into a classroom, the students would all stomp," Daniel says. "Information technology was their signal of derision. They didn't desire coeds at the Academy and I was a woman, so I had no business in that location. And if I dared to respond a question or make a comment, they'd stomp again. So I was stomped my whole way through school."

1945: Full enrollment drops from 2,600 in 1941 to 1,175 in 1945. Women are 18 percentage of total enrollment past the last years of the war.

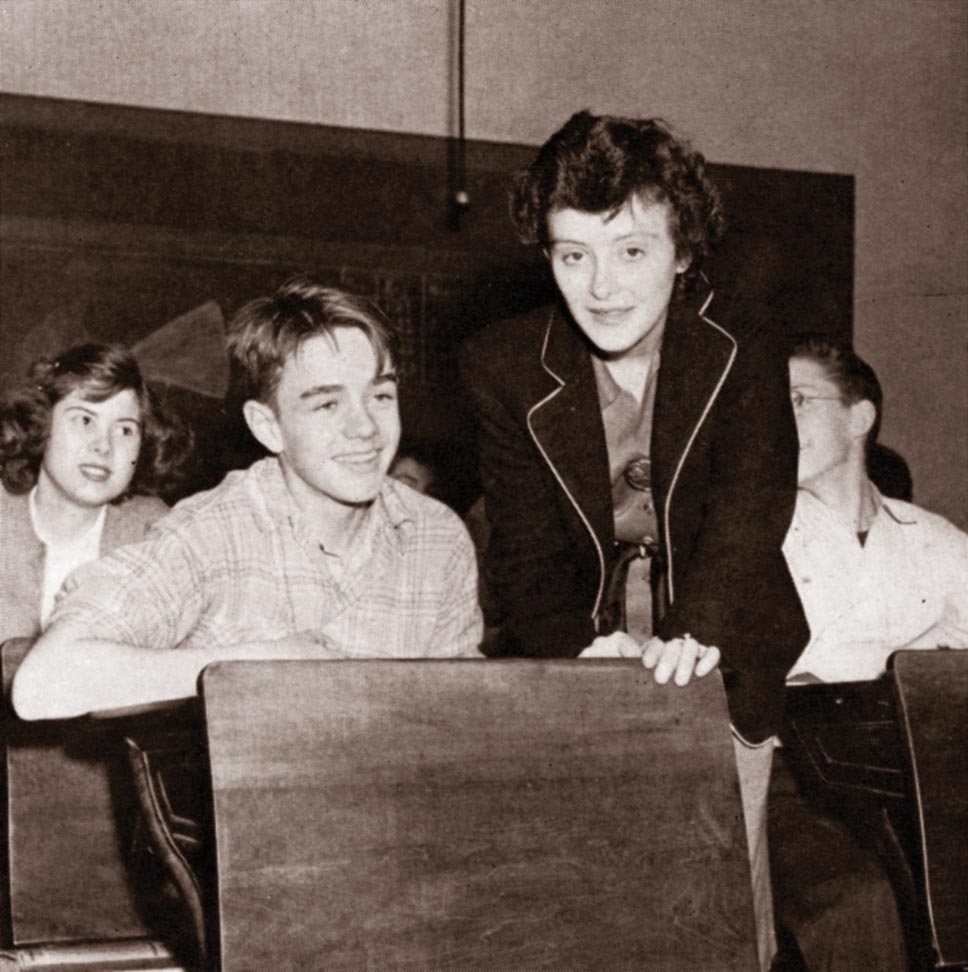

Margaret Sutherland Coleman

argaret Sutherland Coleman (Educ '49) came to UVA from Atlanta when her married man, James Coleman Jr. (Police '51), began Police force School. As undergraduates, women could merely attend classes in the didactics and nursing schools, and then Coleman had to make a determination. "I had two choices: teaching or nursing. I chose teaching and I loved it.

"I just felt like everything virtually Virginia was topnotch," says Coleman. She participated in social activities with her husband's law course, which was already coeducational, and befriended women who were law students. With Earth War 2 just but ended, Coleman remembers the late '40s every bit a particularly serious time at the University, when the newly returned soldiers were catching upwards on their studies. "We were studying a whole lot harder than people are studying now," she says. "Nosotros were all coming dorsum to an empty world. Information technology took a lot of working and caring to make it worthwhile to win that war."

The School of Education

Established in 1905, the Back-scratch Memorial School of Education first admitted women in 1920; past 1922, five women earned degrees from the school in a grade of eight students. From that time on, women constituted the majority of the student body. Indeed, more than half of the degrees conferred on women from UVA between 1920 and 1970 were from the Back-scratch Schoolhouse.

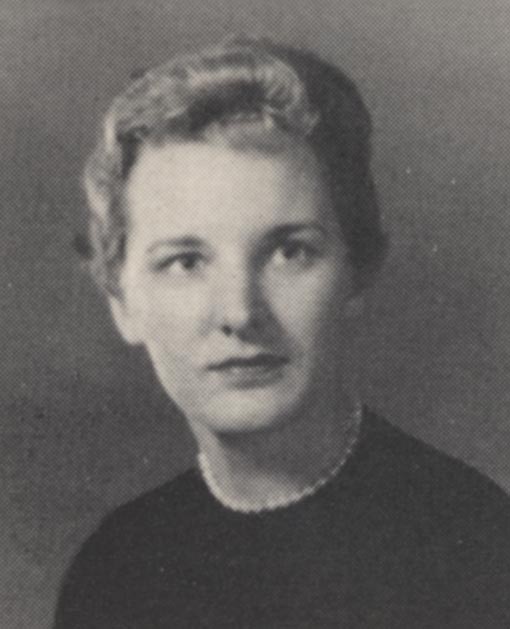

Janet Blakeman

"It was a different time," says Janet Blakeman (Law '57), a New York native who attended the Law School in the '50s. When she lived in a house on Rutledge Avenue that she shared with two other female person students, the dean of women was concerned that her housemate with a private entrance might appear to be doing something unto-ward. "I remember being chosen into the dean's role and asked if men were visiting the house late at nighttime!"

Blakeman, who went to Wellesley College, came to UVA having never been to Virginia. "I was looking for constabulary schools that had some female students," she said. "Virginia sounded like a nice place. I took the train. I thought it was cute."

It was just after the Korean War, and Blakeman found herself attending the school with a number of veterans. Her class of about 150 students included only one other woman. In a field yet dominated by men, they experienced their share of discrimination.

"I recollect a male person classmate who said to me, 'You're taking the identify of a man who has to support his family unit,'" says Blakeman.

"Almost of my classmates were pretty nice to me," she explains. "But there were some who didn't seem to similar the idea of having a woman in the class."

However, Blakeman plant a lot of happiness in her studies. "I have to say, I enjoyed being called upon, having to recite and studying in the carrels in the library.

"And we had fun," she says. "Anybody went to the Corner, Carroll'due south Tea Room and Fry'due south Spring Beach Social club. Married students would accept parties; there were football games."

Blakeman worked in trusts and estates constabulary in New York for four decades. And what of that quondam classmate who accused her of taking another homo's chore? "I saw him later," Blakeman says. "He asked me what I was doing. I said, 'I'm supporting my family!'"

Ann Kiessling

In 1960, Ann Kiessling (Nurs '64) was at a crossroads. She'd just graduated from high school and knew she wanted to go into scientific discipline, but wasn't quite certain how. She'd narrowed it to two possible avenues: medical school or research. She enrolled in the nursing program hoping it would assist clarify her real passion.

"One of the well-nigh positive experiences was the infirmary feel," she says. "At the time, the nursing students were given a great deal of independence, and the medical staff treated us non much differently from the way they treated the med students."

Ane highlight was working with Dr. William H. Muller, who was then the chairman of the section of surgery. At the time, open-heart surgery was a relatively new procedure, and he had developed one of the replacement heart valves. "I was invited to team meetings," says Kiessling, "because I'd shown such an interest. I was interested in the logistics of how they were going to bypass the middle, how the equipment was designed, how they were going to oxygenate the patient."

Kiessling ended up choosing research. Afterwards obtaining subsequent degrees, including a doctorate in biochemistry and biophysics, Harvard recruited her in 1985; in 1996, she founded the Bedford Stalk Jail cell Research Foundation.

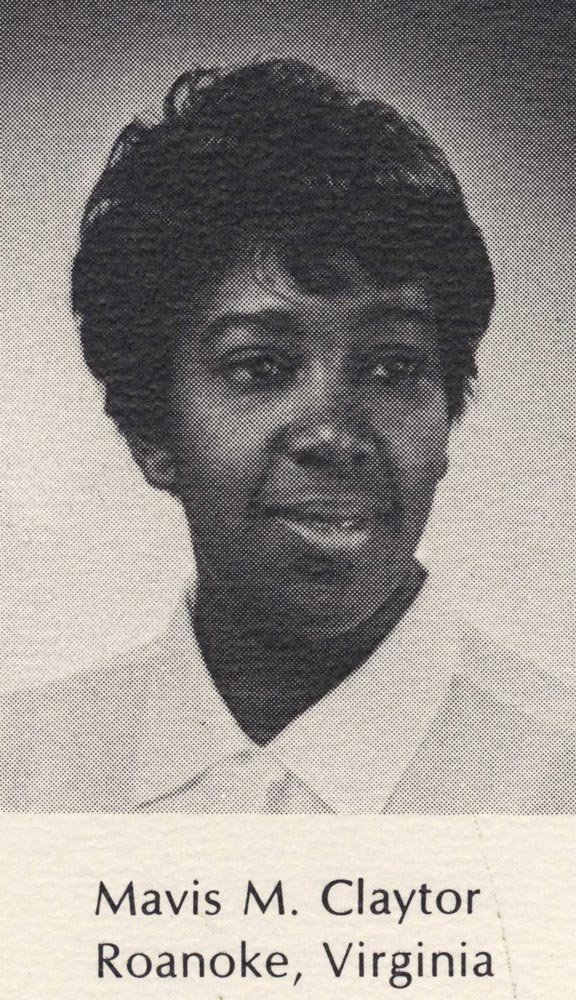

Mavis Claytor

When Mavis Claytor (Nurs '70, '85)—the start African American to earn a caste in the nursing school—arrived in Charlottesville, she stayed at a hotel for a month because she was unable to secure housing in the student dorms as a black educatee. When she ran out of money for her hotel room, she sought aid from the dean of the Nursing School, Mary Lohr (Nurs '62), who was able to assistance discover a room in the dorms. Yet, when Claytor speaks of her education at UVA, this initial hardship appears to be a minor setback. "I was so focused on getting my educational activity that I did not pay attending to the fact that I was the only black student," says Claytor.

She oftentimes returned to her hometown of Roanoke on the weekends because she missed the comforts of her abode and community, but at UVA, Claytor was a driven student. Already a registered nurse, Claytor was a popular report partner because of her feel and knowledge. She was asked to bring together a sorority but declined.

When she was 16, Claytor cared for her ailing grandmother and decided and so that she wanted to become a nurse for the elderly. She worked every bit a licensed practical nurse in Roanoke until she was offered a scholarship at Helene Fuld Nursing College, where she became a registered nurse. She wanted to go to UVA for her bachelor's degree because it was an accredited schoolhouse, but she considered the move somewhat risky. "My family was limited financially and I knew I would just have that i opportunity, so I wanted to practise the best that I could. I was determined: This is going to exist it for me."

Claytor found a mentor in Jeanne Cutler Fox (Nurs '68), an teacher in the Nursing School who encouraged Claytor to pursue a main'south caste in nursing. At this time in the University'due south history, Claytor could see more doors opening for women. "I felt that that was a expert time for females to enter any program that they wanted to." Claytor recently retired as the principal of geriatric nursing at the Veterans Affairs Medical Centre in Salem, Va., after a career of 30 years.

"At UVA," she says, "we didn't retrieve that much in terms of race or gender. I think we were just focused on the educational climate at UVA. We e'er had football games and activities that brought people together. Times were start to change chop-chop."

The School of Nursing

In 1901, the UVA hospital created a nurses' training program, which granted diplomas to thousands of women over the next 50 years, but was non recognized as part of the academic offerings of the Academy until 1949. Nursing students initially lived in rooms in the attic of the infirmary building. Patient overcrowding in the hospital and a measles outbreak resulted in the accommodation of Varsity Hall in 1914 from its initial use as an infirmary to accommodations for nursing students. Nursing students went on to live in Randall Hall, starting in 1919, and McKim Hall, which was built in 1931. The School of Nursing became an contained school of the University in 1956, with Margaret Gould Tyson the school'south showtime dean. Men were admitted in 1962; the first male pupil, Thomas Watters (Nurs '66), had been a U.Due south. Navy corpsman.

Mr. Jefferson's Nurses by Barbara Brodie details the school's ban on marriage for nursing students. Even into the mid-'50s, faculty would vote on whether to allow a nursing student to ally without leaving the program.

Full Coeducation

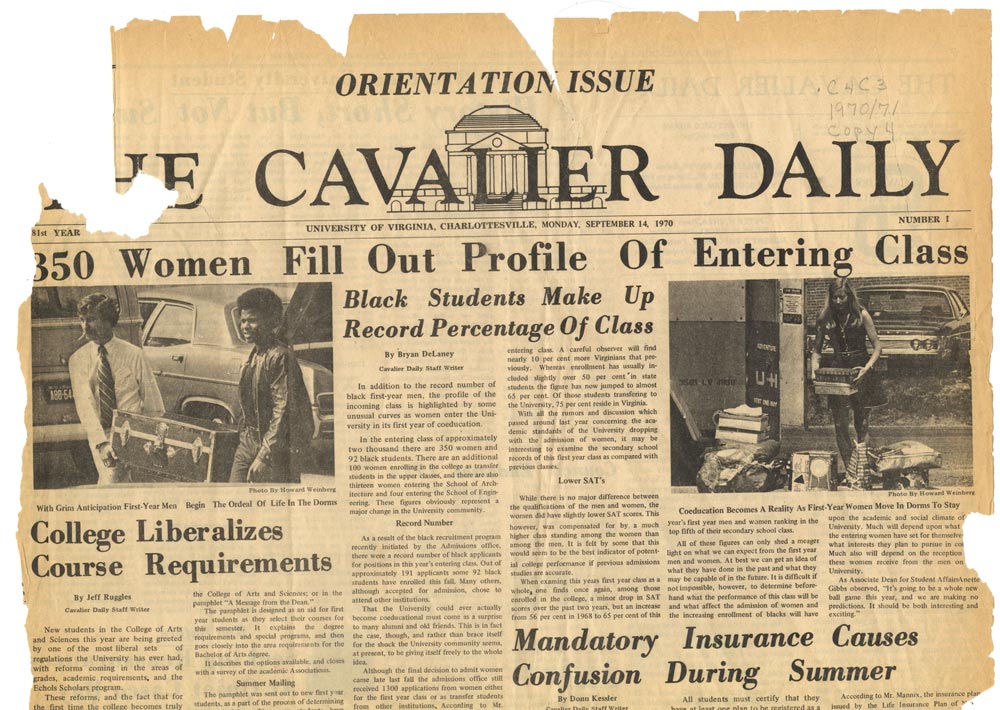

In the mid-'60s, members of the Virginia General Associates and several state commissions encouraged the University to consider full coeducation. African Americans had fought for access to the University and, starting in the late 1950s, UVA had begun admitting small numbers of African-American students.

In early 1969, the Board of Visitors voted to gradually provide greater access for women to all parts of the University. During a transitional catamenia of one year, they planned to admit the qualified wives and daughters of staff members. The University proposed increasing the number of female students over x years and capping their number at 35 percentage.

Mere months later, four women—Virginia Anne Scott, Nancy Jaffe, Nancy 50. Anderson and Jo Anne Kirstein—represented by American Ceremonious Liberties Union lawyer John Lowe (Law '67) brought a lawsuit confronting the Academy. The plaintiffs claimed that the University "severely discriminates against women in their admissions policies" and petitioned for the College to admit women.

The courtroom mandated full coeducation within three years. The court as well granted the plaintiffs a temporary injunction to study in the College of Arts & Sciences in the autumn of 1969 rather than having to wait an additional twelvemonth. Virginia Anne Scott enrolled that semester.

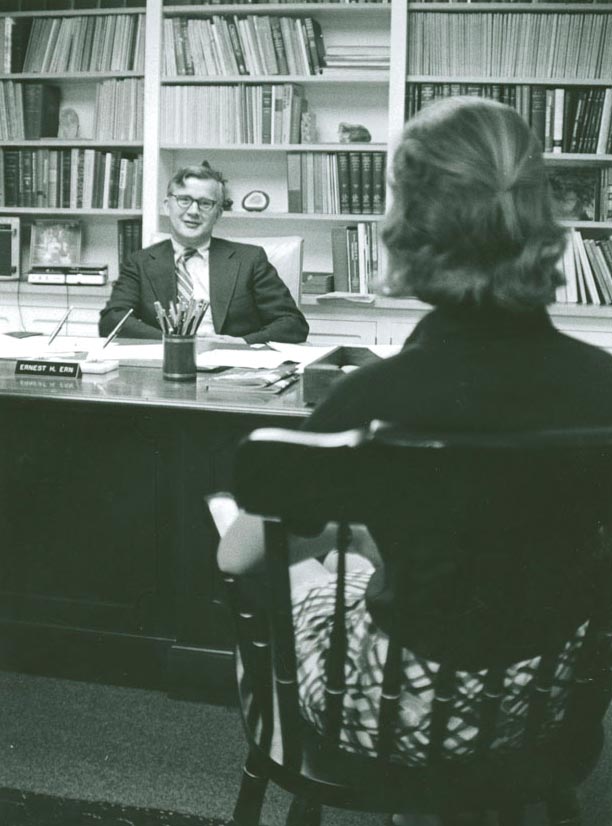

In September 1970, 450 undergraduate women, 350 of whom were first-years, entered the College. Ernest Ern, admission dean during those transitional years, was quoted as saying that the Office of Admission intentionally selected exceedingly strong women who displayed bookish, leadership and social promise.

In 1971, 550 new female students arrived on Grounds. The fall of 1972, students were admitted without regard to gender. These women gained entry into UVA's organizations, societies and leadership positions, including the IMPs, the Raven Society, the Cavalier Daily and the Honor Committee. In 1972, Cynthia Goodrich Kuhn (Col '73) moved into 28 East Lawn and became the beginning female Backyard resident.

Student Life Earlier 1970

- 1921: Adelaide Simpson becomes first dean of women.

- 1921: The Women Students Cocky-Government Association is created.

- 1927: Mary Jeffcott Hamblin becomes dean of women.

- 1928: The Co-Ed Room on the West Range provides a women-simply space to gather for meals or other social events.

- 1934: Roberta Hollingsworth (Grad '33) becomes dean of women.

- 1951: Mary Munford Hall is the beginning dormitory built specifically for women.

- 1967: Mary Whitney becomes dean of women.

- 1970: Annette Gibbs, associate dean of student diplomacy, helps with the transition to full coeducation.

A history of female professors at UVA

1963: First Female Full Professor

Doris Kuhlmann-Wilsdorf joins the Academy in 1963, condign the commencement female total professor, and continues equally a professor of engineering science for twoscore years.

Previously, she'd worked every bit a lecturer in physics in South Africa and was a professor of metallurgical technology in Philadelphia. Kuhlmann-Wilsdorf was a member of the National Academy of Engineering, wrote more than than 300 scientific papers and started ii companies, HiPerCon, for loftier-functioning electrical contacts; and Kuhlmann-Wilsdorf Motors.

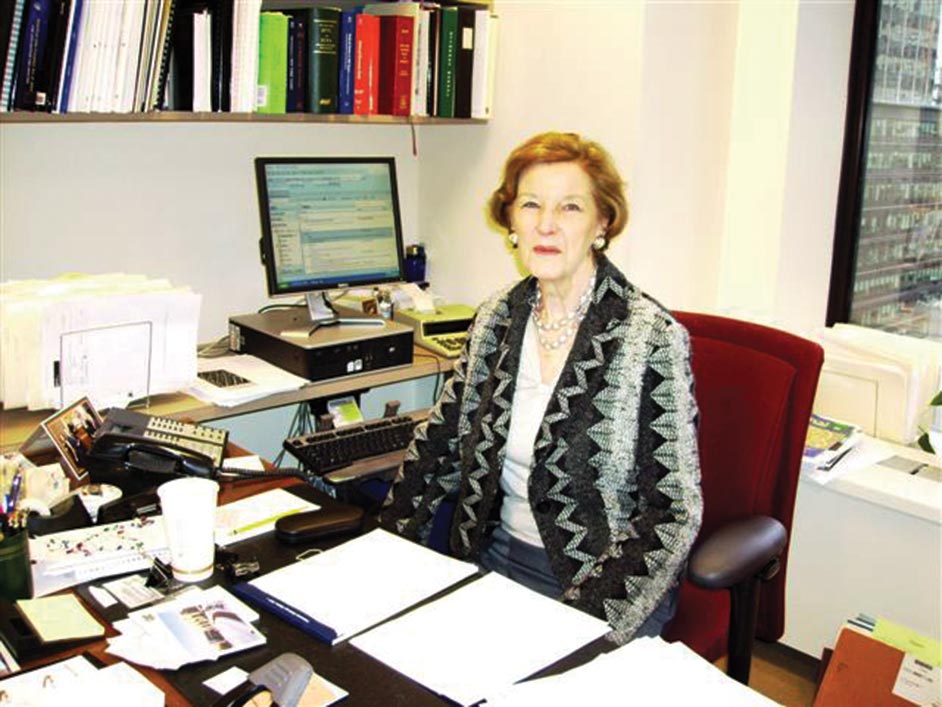

1973: Commencement Female Tenured Law Faculty

Lillian BeVier joins the Police force School faculty in 1973, later saying, "I must take seemed similar a very strange person to the people in Charlottesville—I was a woman, I wanted to be a constabulary professor, I was divorced, I had two kids, I drove a '68 Chevy Camaro convertible—simply they were and then nice to me." She retired in 2010.

1979

There are 206 female faculty members and i,171 male kinesthesia members at the Academy.

2008

There are 688 female faculty members and 1,483 male person faculty members at the University.

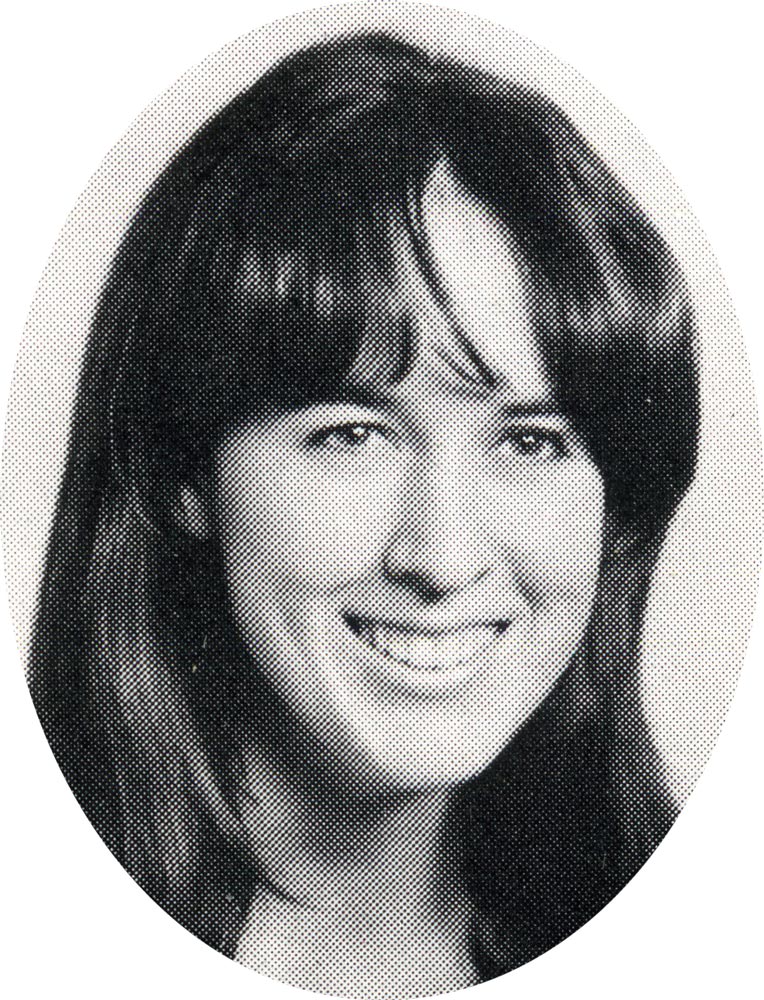

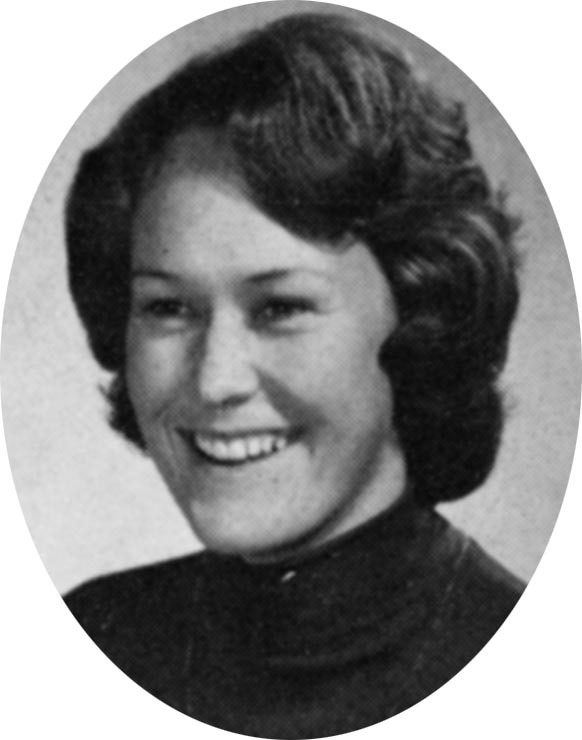

Holly Smith

Holly Smith (Col '72) was in her sophomore year at Sweet Briar College when she heard that UVA had opened its doors to female undergraduates. She practical and was happy when she got in. "Patently Dean of Admission Ernest Ern purposely chose female applicants who were agile and aggressive. It was fair to say I fit that beak," says Smith.

During the summer earlier she arrived at UVA, Smith discovered Our Bodies, Ourselves, a book significant to the women's move of the '60s and '70s. "It explained that women were equal to men and should be treated equally," says Smith. "With my outlook on life rearranged, I arrived in Charlottesville in September of 1970 prepare to do boxing in the cause of making sure that women were given equal treatment at the University."

Times were turbulent. Smith remembers protests against the Vietnam War, but she found that male person students were by and large pleased to accept women at the University. "There was a tradition, though, that no male student would sit next to a female student in class unless all the other seats were taken. Frequently the men were only shy, non resentful."

Peradventure because the Academy had to quickly comply with a 1969 court club to admit female undergraduates, Smith noticed some areas of student life where the Academy did not adequately provide for women's needs. She joined the staff of the Cavalier Daily and wrote well-nigh UVA'southward transition into a fully coeducational institution. She covered topics such as the development of health treat women on Grounds and attitudes toward women'southward athletics. In 1970, women seeking birth control were directed by Educatee Health officials to become care from physicians in the city of Charlottesville. Athletic scholarships were awarded only to men.

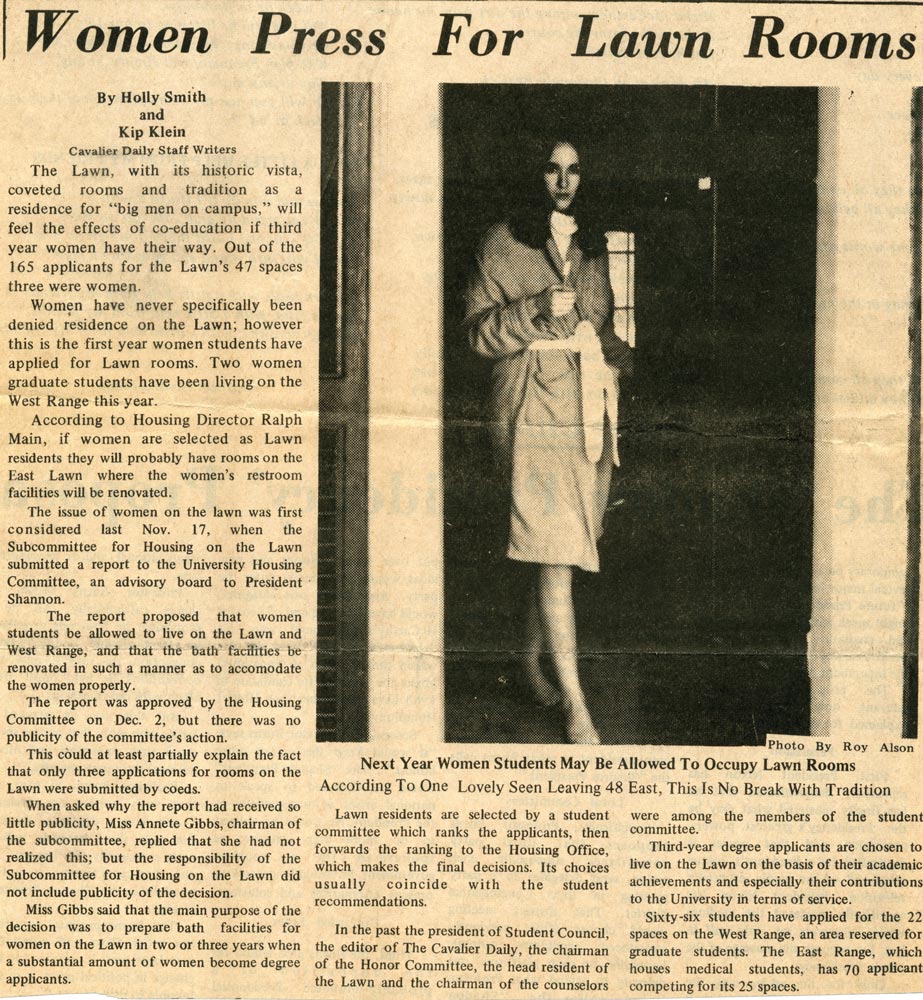

Smith likewise tackled the controversy almost opening upwardly Lawn rooms to women. In an interview, Smith asked Ralph Main, director of housing, why women couldn't live on the Backyard. "Bathrooms," he told her.

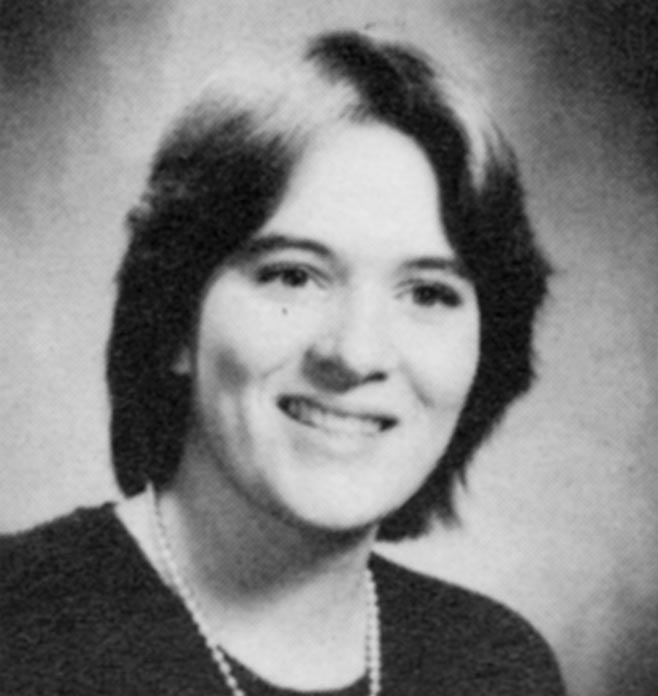

Valerie Smith Kirkman

Although Valerie Smith Kirkman (Nurs '75) and her sister, Holly Smith, were both students in the early '70s, they had very unlike undergraduate experiences. While Smith ran into some speed bumps as one of the first female undergraduates, Kirkman says that when she arrived two years later, women had already assimilated into University culture. "I recall the transition happened pretty quickly," Kirkman says. "Because I came in the fall of '72, women had already been in that location long enough and the men were used to women being around."

She says her fellow nursing students were career-oriented like her and that nursing was a career that was flexible enough to fit several life stages. "I loved nursing considering it immune me to work part time when we were raising kids, or to accept a break and go back into it."

During her 3rd year, Kirkman was a cheerleader and remembers how the men from the fraternities traveled to nearby universities to pick upwardly dates to bring to football games and big weekends. "1 thing I noticed," she says, "is that the girls who were from UVA would wear bell-bottom blue jeans, while girls who were imports from schools like Sweet Briar wore plaid skirts and matching sweaters."

Kirkman says that the women's movement wasn't a major issue on Grounds. "We knew that women could do whatever they wanted to practise," she says. "Information technology was merely an attitude of knowing that."

Sandra Lewis

"My reasons for choosing UVA were non quite the usual ones for selecting a higher," laughs Sandra Lewis (Col '72). When she finished high schoolhouse, the College of Arts & Sciences did not have women equally undergraduates. Born and raised in Charlottesville, she met her husband-to-be, Lemuel Lewis (Col '69, GSBA '72), while he was a UVA student. She attended Fisk Academy in Nashville while Lemuel was at UVA. They married a year later on and she enrolled at UVA in 1969 as a 2nd-year "day student." Lewis was later accepted every bit a regular tertiary-year pupil in 1970 with the arrival of total coeducation.

"I did non encounter whatsoever resistance from anyone that I tin recall," says Lewis. "I found that the male students were for the virtually part very gentlemanly." Her perspective might have been different had she been unmarried, she says. Lewis lived in married student housing and socialized with other married couples.

Lewis describes a somewhat polarized campus. "I was at UVA when the Vietnam War was going on," she says. "We had very traditional, necktie-wearing students and then we had the '60s radicals. UVA had its set of protestors, and then there was a little more going on than only your football games and frat parties. It was a campus that was in an uproar.

"The only negative feel was that even though in that location were African Americans attending at the time, I don't think there was a lot of integration of the group into the campus life," she says.

Thinking back, she describes graduation as an peculiarly meaningful day. Her begetter worked as a chemist's shop banana in the UVA hospital and her grandfather had been a groundskeeper for the University. "Even though they were not part of the bookish setting, they still had pride in the school," she says. "My father had grown up seeing all-white football game games and students, then him existence at that place fabricated it very special for me, knowing how he felt most his girl graduating from a school where he was in the shadows."

Tanya Lewis

Of the many reasons a teenager might pick i university over some other, Tanya Lewis (Col '00) had a special one for attending UVA. Both of her parents were alumni. Her father was among the outset African Americans to graduate from the Darden concern schoolhouse, and her mother, Sandra Lewis (Col '72), was the first African-American woman to graduate from the Higher of Arts & Sciences. "I was very familiar with the campus and the history and the reputation," says Lewis.

"It was enlightening," she says of her time at the Academy. "I came from a earth in which I was sheltered—I'm an only child, so I had to do the roommate matter." She was also torn virtually her conclusion to major in Economics and follow in her father's footsteps. "I wanted to exist certain that I was creating my own hereafter," says Lewis, "and for the first time I had to brand a major decision independently of what my parents saw for me. I knew that fewer women chose economics as a major, which was really more than motivation for me to stick to my ain plan. Fortunately, my parents wholeheartedly supported my decision."

If she has 1 regret, information technology's that she was never able to strike the perfect balance between schoolwork and extracurricular activities. "I was strictly academic," she says. "I wish I could have been more than involved."

Lewis got a B.A. in economics at UVA, and went on to spend half dozen years in banking, then worked in real manor. Now she's at Georgia State University, taking the prerequisite classes needed to use to nursing schoolhouse. "I've ever been more than of a people person," she said. "I like the sales stuff, but not the highly competitive cut-throat sales that I was doing. I'one thousand trying to bridge the business side of myself with the more nurturing side."

"I can't believe it's been 10 years," she says, thinking dorsum. "The friends I have at present are pretty much the friends I made in college." How did she feel on graduation day, continuing a legacy started past her parents? Lewis laughs and says, "Relieved."

Women'southward Athletics

Earlier 1970, in that location wasn't a women'due south athletics program at the University, even so UVA nonetheless boasted several notable female athletes, including Mary Slaughter (Educ '54), who lettered in tennis in the early on '50s, and Mary Brundage (Nurs '67), who competed alongside male swimmers on the 1966 varsity swim squad.

In 1972, Championship Ix became law. In add-on to ensuring equal job opportunities for women, it mandated that educational institutions provide equal opportunities and funding to men's and women's athletics programs. In 1977, UVA awarded its commencement athletics scholarship to a woman.

Today, the Virginia Athletics Foundation provides more $4 million in scholarships to women athletes.

Jill Haworth Jones

Some days during cantankerous country do, Jill Haworth Jones (Col '83) would hop a debate, cantankerous a cow pasture, pass the mansion on the hill and run around the dorsum of the present-day Birdwood Golf Course. Other days, she would run well-nigh the polo fields and loop around. "The clay paths on O Hill, the athletic fields—sometimes we'd run around the Corner," she says. She and the other members of the women's cross state team ran up of 70 miles a week.

Jones and her teammates made UVA history when they won national championships in 1981 and 1982. "The first year was exciting, just the second year might have been an fifty-fifty sweeter victory," says Jones. "The 2nd year, 2 of our best athletes, Lisa Welch (Educ '85) and Aileen O'Connor (Col '83), couldn't compete due to injury, and the motorcoach at Stanford was quoted in a paper equally saying that nosotros should mail him the trophy. But we won."

Jones was among the first women to be offered athletic scholarships at the University and an early beneficiary of Championship IX. "I know it opened up a huge door for me personally. Information technology has changed a lot of women'due south lives," says Jones.

Jane Miller, senior associate athletics managing director of programs, concurs that Title 9 "clearly elevated our women's athletics to a higher level with necessary resources to compete at the highest levels." UVA introduced women's varsity sports in 1973, awarded the first scholarship to a female student-athlete in 1977, and by 1980 was supporting 10 women'south varsity sports. Currently, there are 13 women'south sports. "In the last 10 years, we've reaped the benefits of fully funded scholarships for our female student-athletes. In 2009-10, 12 of our teams participated in NCAA championships. The rowing team won its showtime national championship in the spring," says Miller.

What was it like to be a pioneering female student-athlete? Jones says that she had little time to participate in social activities. "We were either studying or running," she says. "The cross country team was my sorority, a very close-knit grouping. Head coach Dennis Craddock and cross country coach Martin Smith kept us very busy."

Jones was a nine-time All-American and competed at the national level in track and cantankerous state. She was twice a finalist for the i,500 meters outdoors at the Olympic trials.

Nancy Andrews

Nancy Andrews (Col '86) is an award-winning photographer and managing editor for digital media at the Detroit Free Press. She's won 3 Emmys for her video production work and published two books of photography. Only earlier all that, she was a young woman growing up on a small farm in Caroline County, Va., thinking about college, and entranced by the idea of UVA.

"I loved everything it stood for," she says. "I read all about Thomas Jefferson, and I loved the philosophy of the place."

She enrolled and got a degree in economics, but cites the Cavalier Daily as her real major, where she served at various points equally the lensman, photograph editor and managing editor. It was a trial by fire experience, she says, and set the groundwork for her future career as a successful photographer and journalist. "It was one of the hardest jobs I've ever done," she says of putting out a student-run, v-days-a-week publication. "We ran that newspaper."

Andrews recalls her experience at UVA as an enriching, multi-faceted and exciting fourth dimension. And an especially pivotal time—she came out as a lesbian.

"I knew information technology was correct," she says. "I had learned this nigh myself. And I knew there were people that wouldn't agree." She explains that it was the mid-'80s, a dissimilar landscape in terms of the credence of gay people, and that some of the reactions she got were perchance a reflection of her own feelings, which were a little fearful. However, she claims that the overriding outcome was back up. "Did my friends change as a outcome? Absolutely not. I can't really say annihilation negative happened."

After stints at a Fredericksburg, Va., newspaper and the Washington Post, she moved to the Detroit Gratis Press. In addition to her paper work, she'due south published a book of photography Family: A Portrait of Gay and Lesbian America and ane well-nigh a friend of hers who had Alzheimer'southward, which contains photography and spoken testimony called Partial View: An Alzheimer'southward Periodical.

After graduating, Andrews says she heard about some anti-gay sentiment at UVA, and then she asked a one-time teacher if she could visit and talk to students.

"Cypher like talking to 400 people and telling them y'all're gay," says Andrews. Though she struggled through the talk—"I don't think what I said, I but retrieve that I talked about it"—the students were receptive and asked thoughtful questions. "I think it was good for the students. They're all part of moving things forwards."

Women's Studies at UVA

UVA founded the Women's Studies Program in 1979 and appointed Sharon Davie (Grad '69, '72) its director. The programme ran kinesthesia development seminars in women'southward studies and launched Iris: A Journal About Women. In 1989, at the recommendation of the Task Force on Women, initiated past President Robert G. O'Neill, the Women Studies Program split into the academic program and the Women's Center, which provides services to students. In 1990, Ann J. Lane became director of the academic program, now a major, and the first UVA student graduated in the field of women's studies.

Glynn Key

One afternoon, when Glynn Central (Col '86, Law '89) and two female friends were chatting outside Key'due south Backyard room, they witnessed a rowdy football game player throw a piece of firewood through ane of the Pavilion windows. Fundamental and her friends chased the player, tackled him and kept him at bay while one of the women ran to call the police. "I heard subsequently that the coach kicked him off the team," says Key. "He would have usually been suspended, merely he was kicked off because the bus didn't like that he was tackled by 3 girls."

Every bit a student, Fundamental was dedicated to academics and extracurricular activities; she was a Jefferson Scholar, the chairman of the Honor Committee, and a member of Delta Sigma Theta, a predominately black sorority. Key after became the president of the Alumni Clan's Board of Managers and a member of UVA's Lath of Visitors. "I consider myself very competitive, and I think that was something that was nurtured at Virginia. I had a want to do the best at whatsoever it was," she says.

Equally an African-American woman, she found UVA's customs to exist supportive of her desire to excel. As the chairman of the Honor Commission, she says that other concerns were far more pressing than race or gender. "Information technology was a larger outcome of the gravity of the single sanction system and what you had to acquire virtually yourself and other people," she says.

From the moment she arrived at the University, Key appreciated the benefits of a big, vibrant community. "I think UVA is a identify where yous're able to be exposed to things that are new," she says. "Yous are allowed to bring yourself into traditions at the University, whether as a woman or equally a minority. To me, it's a drove of communities that are centered around core values."

Still, Cardinal, who now is general counsel for General Electric, recognizes that she and her peers were frequently pioneers. "I would bet that of the women who graduated in the '80s, yous'll find out that they were the first minorities to hold certain positions in their fields."

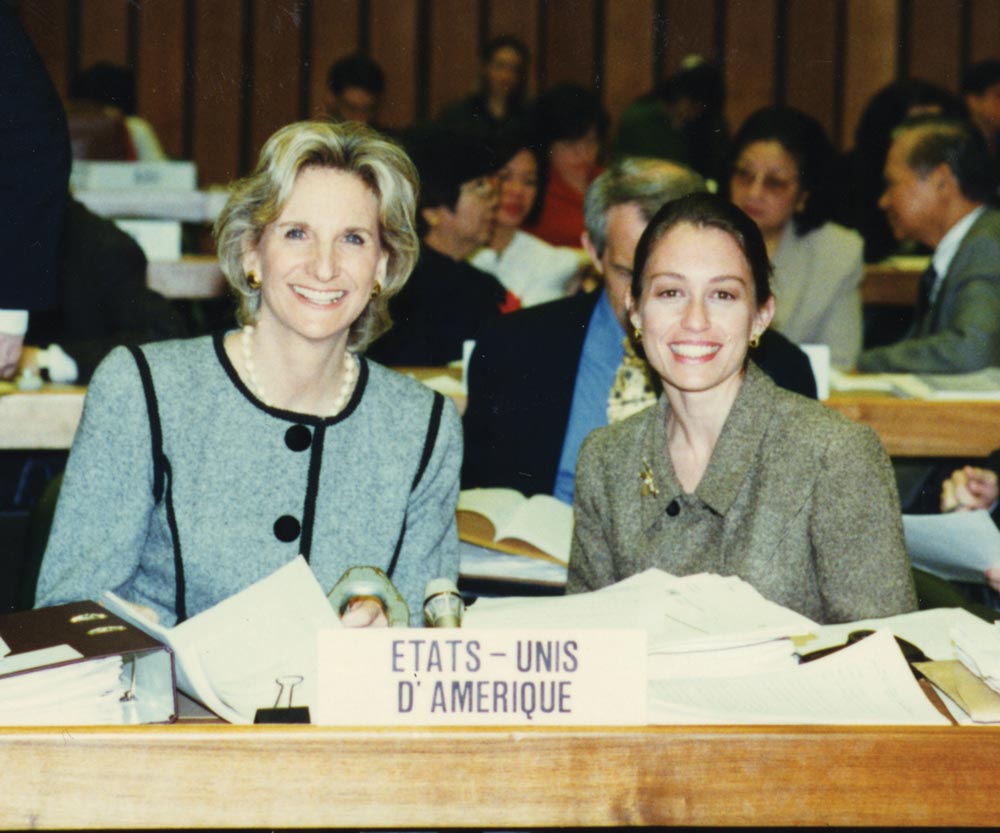

Alexandra Arriaga

"You are not girls, you are women!" Sybil Todd, associate dean of students, told Alexandra Arriaga (Col '87) and her fellow undergraduate women.

The signal was well made. "She made it clear that our contributions were important and valid, that nosotros had something to bring to the table," says Arriaga. "Coming of historic period in the '80s, nosotros were building on all the piece of work that had been done past women in the '60s and '70s. Oft, women of my generation were the outset women to work the jobs that we worked. We were affirming hard-won rights and making them into realities."

Arriaga majored in Latin American studies and participated in the Laurels Committee on Grounds. "My peers were other women who had studied really hard in loftier school, so I felt I fit in," Arriaga says. "There weren't many people who had an international background and I didn't self-place as a minority."

Arriaga's parents were both immigrants to the U.S., her begetter from Spain growing up in Argentine republic and her female parent from Chile, and the family spent time in Chile during Arriaga'south teen years. "We were there a few years after the military machine insurrection. I retrieve the riots, the curfew and how people fighting for free and open up voting were mistreated." These experiences brought to her attention the importance of human rights. "I became more enlightened of the disparities and appreciative of the freedom enjoyed in the U.S.," she says.

Later on graduation, she worked and volunteered in Washington, D.C., quickly rising to become manager of the Congressional Homo Rights Caucus. In 1995, Arriaga worked for the Land Department as a senior adviser to the assistant secretary of state for democracy, homo rights and labor. Arriaga was a consul to the U.N. Commission on Human Rights and led the agency's Working Grouping on Women's Human Rights. "Focusing on women'south human rights, yous learn that where women are respected democracy has a far greater chance at success. What is good for women is good for everyone," says Arriaga.

Later on two years in the White Business firm during the Clinton administration as a special assistant to the president, she worked for Amnesty International USA, and then started a consulting firm. In all of her jobs Arriaga has traveled extensively, visiting more than 40 countries. "Many times I was the but woman in the room."

Arriaga will receive the UVA 2011 Distinguished Alumna Award.

Melissa Stark Lilley

Some of Melissa Stark Lilley's all-time memories are of sitting in the student section of Scott Stadium watching football games. "I've e'er loved the ambiance around sports: the camaraderie, the ritual, everyone meeting with a shared want to win," says Lilley (Col '95). She wasn't just a spectator for long; she became a production assistant and reporter for Virginia Basketball with Jeff Jones and Virginia Football game with George Welsh, where she profiled players and covered games. "Information technology was a good time for UVA sports. Men'south soccer won national championships and women's lacrosse won the NCAA championship twice," she says.

After she graduated, Lilley took samples of her work for UVA athletics to news and sports directors and got a chore covering sports in Washington, D.C., and Baltimore for Play a joke on. Next she was hired by ESPN every bit a SportsCenter reporter and occasionally anchored for ESPN news. When she was 26, she got the job for which she is best known—equally a sideline reporter for Monday Night Football. "There weren't a lot of women in sports journalism," says Lilley. "In that location were a few who came before me, but it was however rare.

"Amongst the athletes, there were a few of the quondam guard who felt uncomfortable with women talking to them about sports," says Lilley. "Jack Nicklaus once said something to me to that effect, but the younger athletes, similar Sergio Garcia, know that times have changed."

After a few years as a correspondent for the Today Show and covering three Olympics, Lilley decided to intendance for her four children full fourth dimension. "These children and my family are my existent legacy," she says. "When people talk about the impossibility of having it all, I'thousand not sure what that means. For me, this is having it all."

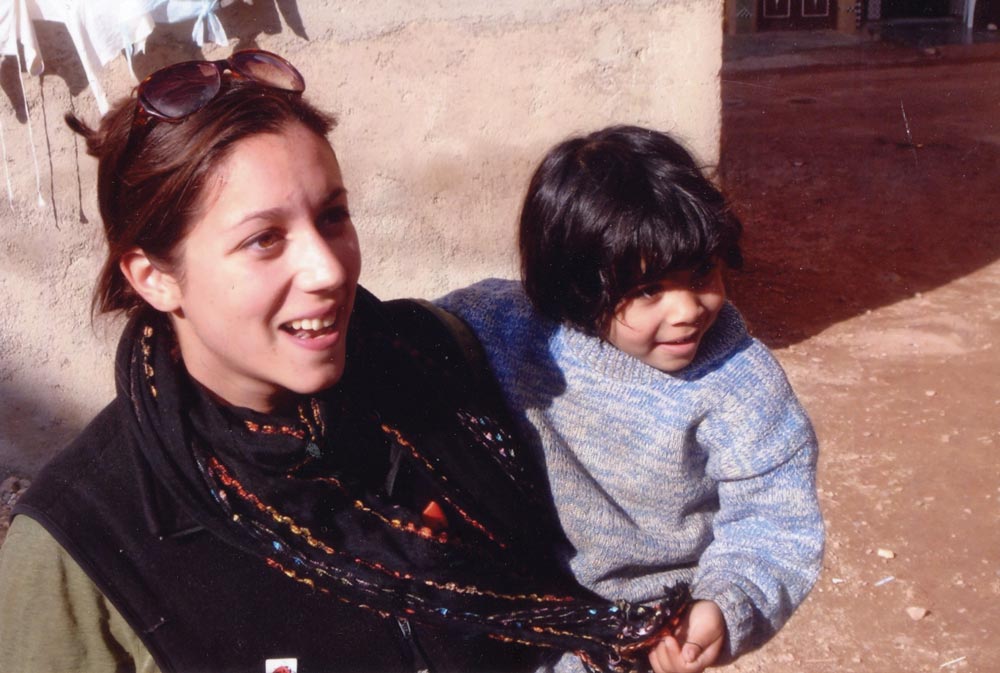

Mary Elizabeth Bruce

Mary Elizabeth Bruce's real instruction began not at her high school in suburban Ohio or even her first twelvemonth at UVA, but in an simple school classroom in Washington, D.C. She spent a yr before college working with AmeriCorps in inner-city schools plagued by poverty. "Some of the 10-yr-olds that I knew wouldn't graduate from high schoolhouse. Some would be victims of violence and wouldn't even meet their 18th birthdays," Bruce (Col '04) says. "I knew that I wanted to study something that would help me address these very real problems."

Bruce arrived at UVA with clear academic goals around which she congenital a curriculum that dealt with social and economic inequality related to race, gender and poverty. "Econ 101 didn't resonate with what I'd been working on," says Bruce. With the support of the Middle for Undergraduate Excellence and mentor Professor Wende Elizabeth Marshall, Bruce earned her degree in a new interdisciplinary field, poverty studies.

Bruce was the co-president of the UVA chapter of the National System for Women and chair of the Minority Rights Coalition. "Being a white woman in that position was a unique challenge that year where in that location were conflicts on Grounds related to race and identity," says Bruce. "A student running for president of student council was assaulted; a graduate educatee was murdered in her dwelling house in an incident of domestic violence; students protested the Cavalier Daily for its portrayal of race bug on Grounds." In response to these issues, the Minority Rights Coalition helped institute Kaleidoscope, a middle for cultural fluency at Newcomb Hall, which invites speakers on multiculturalism and provides other variety-related resource to students.

Bruce helped organize Have Dorsum the Dark, an almanac march intended to bring light to problems related to domestic violence. "I felt very conscious of what it ways to be a adult female in our culture; it was a large part of my day-to-24-hour interval identity," she says. Bruce worked with the Women's Center to brainwash virtually the role of women leaders at UVA. She started a women'southward running gild. She worked to provide resource for women on Grounds. "Nosotros had a mechanic come up and talk to usa about fixing cars. Information technology was information our boyfriends knew and we needed to know," says Bruce.

"One of the biggest challenges for women in the U.Due south. remains economical inequality. It is still true that a woman graduating from UVA volition exist paid less than her male counterpart," says Bruce. "Improving the situation of women volition atomic number 82 the way to a fairer society, healthier children—the list goes on."

After graduation, Bruce joined the Peace Corps and went to Kingdom of morocco where she worked at a youth center. Her 27 months in Morocco revealed a dissimilar office for women than in the U.S. "One of the smartest girls I tutored was withdrawn from school by her parents considering she'd been engaged to marry," says Bruce. "It was incredibly frustrating to see her opportunities just taken away."

Bruce continues her work in education with Raising A Reader MA, a Massachusetts affiliate of the national non-profit that promotes children'due south literacy in low-income communities. "Children who are provided the tools and resource they need to develop early on literacy skills to enter schoolhouse gear up to learn are more likely to graduate from loftier school, to get to higher and to get skilful jobs."

Irene Kan

Irene Kan (Col '11) spends 60 hours a week in the offices of the Cavalier Daily, where she is managing editor. Between classes, she edits news content and tracks assignments to writers and photographers. "At night, nosotros write headlines and do folio OKs before we transport the finals to the printer for a 1:fifteen a.m. deadline," she says. "A courier distributes the paper on Grounds at v a.m. and by eight a.m. the next twenty-four hours the whole bike starts again."

Kan's studies in comparative literature and political scientific discipline complement the newspaper job. "Certainly, the classroom is a level playing field," says Kan. "I don't think that gender has any bear on on my academic experience." She mentions that the English language department, similar many at the Academy, has more female than male students. "In that location are some brilliant women in my classes. My classmate Laura Nelson was just awarded a Rhodes Scholarship."

Notwithstanding Kan says she was surprised to learn how prevalent traditional gender roles are amid some of her classmates. "I took a class about biological science and gender difference. Discussions revealed that some girls in my course thought of their fourth dimension at the University as a way to become their 'Mrs. Degree' and become full-time homemakers. I don't know any guys who say that."

Her piece of work with the newspaper brings Kan confront to face with controversy and tragedy at the University. Last May, Kan went into the office despite the product hiatus of the Cavalier Daily for finals because she'd heard the news of Yeardley Love'southward death. "I had no staff and missed the last day of my classes. I was on the phone all twenty-four hour period dealing with rumors and trying to make sense of what had happened."

The tragedy brought national attention to the University and raised concerns well-nigh women's safety. Both the assistants and student groups have worked to address these concerns. Kan and other members of her sorority, Sigma Psi Zeta, educate students about domestic violence and concord self-defense classes. Kan says, "Love was a strong person—I promise that we are all inspired by her to stand up up for ourselves and for each other."

Source: https://uvamagazine.org/articles/women_at_the_university_of_virginia

0 Response to "what is the total number applicants at university of virginia and the ratio of men to women"

Post a Comment